(Bloomberg Intelligence) — The need for the Single Supervisory Mechanism to agree on new targets for Greek banks’ bad debt reduction has coincided with cratering bank share prices and investor confidence. We suspect the Bank of Greece and EU regulators will struggle to attract external investment and the European Stability Mechanism, Hellenic Financial Stability Fund and central bank will ultimately carry the can.

The use of Greek banks’ billions of euros of capitalized deferred tax credits (DTC) within a bad bank or special purpose vehicle (SPV) structure may avoid the label of state aid, but it will also raise red flags for some investors, we believe. Details about DTC law and its application from National Bank of Greece’s 2017 Pillar III disclosure offer some insight into how these indefinite life intangibles will be treated, but the fact that they are being considered — in the absence of different, economical ways to raise funds — will deter some investors.

Market capacity to absorb debt and securitized instruments to clean Greek banks’ balance sheets is very limited, at best. Further, the appropriateness of nonperforming-exposure coverage levels is a debate that regulators and the banks will prefer to avoid, we believe.

Contributing Analysts Georgi Gunchev (Banks)

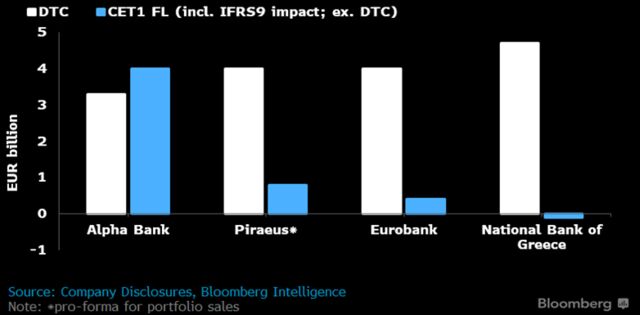

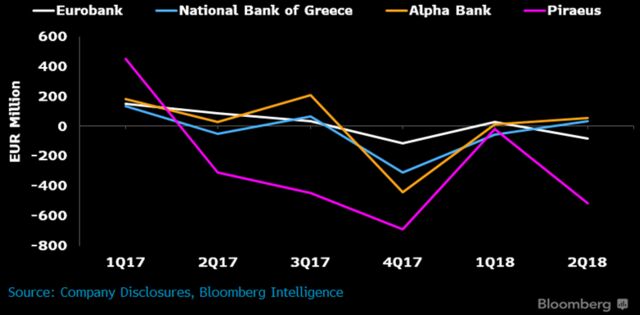

Confusion surrounding the structure, funding and capacity of a bad bank in Greece will likely remain even after details are presented on Nov. 22. A key concern will be where the buyers for debt issued by a special purpose vehicle will be sourced, with Italy, Ireland and Spain also working through legacy issues and absorbing investor capacity. As the graphic shows, deferred tax assets are a core part of transitional capital for the banks. With no likelihood of equity capital raises, any solution must avoid depleting their already scant core capital bases.

The mooted Bank of Greece plan is considerably more complicated and larger in scope than that of the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund, which is based on the Italian model and could relieve the banks of up to 15 billion euros of nonperforming exposure.

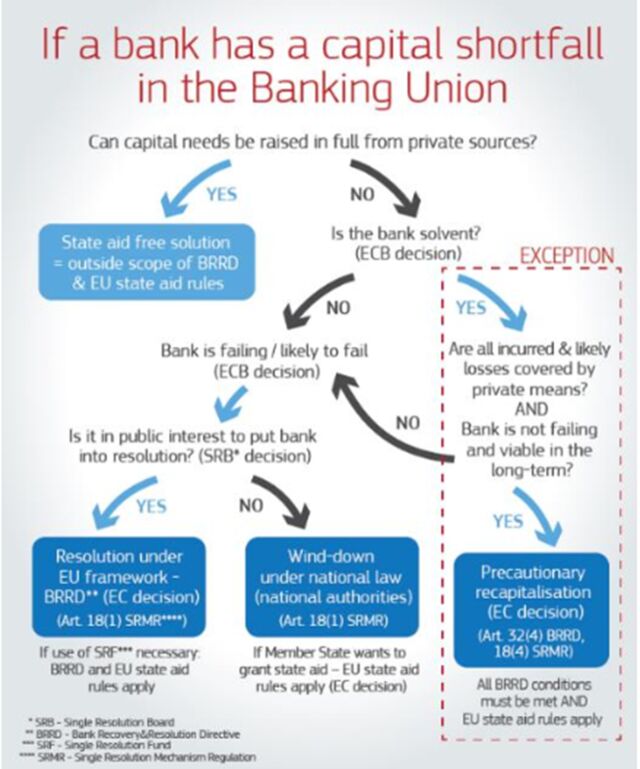

The new Greek cleanup plan could inflict a serious blow to the credibility of the EU bank resolution mechanism. The plan sees the transfer of convertible deferred tax assets (DTA) into an SPV as credit enhancement, which would help the sale of the senior issuance part of the vehicle destined to buy nonperforming loans. The recapitalization of equity reserves created by converting DTA could be achieved through issuance of common shares in favor of Greece. This could be met with skepticism if considered a side-step of the state-aid label.

One controversial precedent of bail-in rule use was the pre-emptive recapitalization of Monte Paschi by the Italian government. There the concern was the discretionary ECB positive opinion on bank solvency and long-term viability. This allowed state intervention rather than burden-sharing.

Contributing Analysts Georgi Gunchev (Banks)

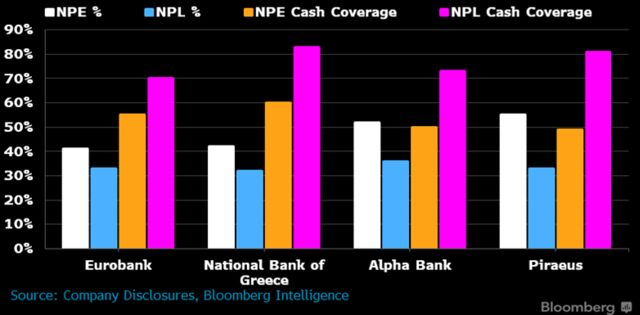

Cash coverage levels for the Greek banks ranged from 49% (Piraeus) to 60% (NBG) at 1H, with both Alpha and Eurobank within the low end of this range. This is in-line with Italy’s more beleaguered banks Banco BPM (51%), Carige (50%), Monte Paschi (56%) and CredEm (50%) which themselves are vying for investors to help offload their bad debt burdens. Curing of these NPEs will continue to be driven by corporate and SME segments, we believe, while the impact of the growing number of auctions on consumer behavior could accelerate organic outflows of NPEs.

Business loans represent two-thirds of Piraeus’ NPEs, with mortgages a little more than 20%. For Eurobank, mortgages (one-third) exceed corporate (30%) NPEs. Mortgages are larger (almost 50%) than SME and corporate combined for National Bank of Greece.

Contributing Analysts Georgi Gunchev (Banks)

Piraeus bank remains the poster child for bad debt cleanup, with 28.5 billion euros of nonperforming exposures at 1H dwarfing less than 5 billion euros of fully-phased in CET1 capital (6.6 billion euros transitional). The approach taken to CET1 calculation, whether transitional — which the regulator will consider — or fully-loaded, which is a default for many investors, makes a significant difference. IFRS 9 and deferred tax assets — and the treatment thereof — are also significant deltas for each of the banks.

For Eurobank, the impact of transition to IFRS9 represented 250 bps of CET1 at 1H, effectively the difference between an 11.9% fully loaded ratio and 14.4% transitional. For Piraeus, the impact was increased 25% to 2 billion euros at 1H, highlighting the enormous sensitivity to accounting approach.

Contributing Analysts Georgi Gunchev (Banks)

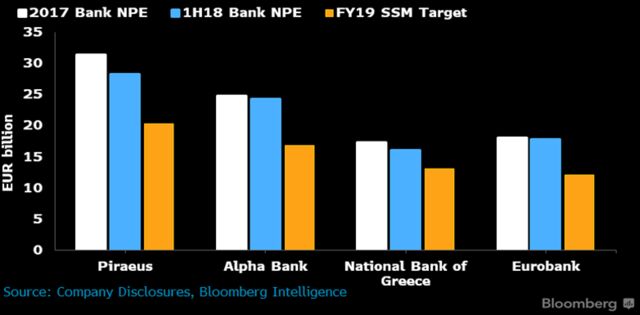

The rate of increase in restructurings and foreclosures, combined with a fall in non-performing exposure inflows, are together critical drivers of how quickly Greek banks’ bad-debt problems are addressed. Should third-party appetite for portfolio sales and securitizations dry up, the SSM will expect banks to absorb higher losses and writedowns, testing the resilience of already-limited cash coverage and fully loaded common equity tier-1 bases.

National Bank of Greece said on its 2Q call that it understood that the target set by the SSM for 2021 would be “aggressive” and as such, inorganic measures would be critical. The ability of banks to absorb further provisions to write off unprovisioned portions of NPEs also explains the need for a greater cost focus, to bolster their pre-provision operating-profit cushions.

Comments ( 0 )